There are no simple systems when it comes to producing energy. One of the most complex parts of the oil and gas industry is the midstream, that multi-faceted infrastructure that gets liquid and gas petroleum from the time it is gathered from the ground to its final destination of a power plant, a ship or a manufacturing facility.

Complicating matters even more is the delicate nature of processing hydrocarbons and transporting them through sensitive environments and populated areas. Regulations abound from numerous federal agencies and state and local governments.

Among the factors to consider are general environmental inspections, clearing, grading, erosion control, sediment control and right-of-way revegetation, trenching, pipe installation, cleanup of both the site and right-of-way properties, and requirements for crossing wetlands and other bodies of water, according to the Southern Gas Association.

The issue of proximity to bodies of water is giving the midstream industry the most challenges because regulators were slow to give guidance on just what the rules would look. That created a hesitancy to pump billions of dollars into new infrastructure to the meet the needs of the nation.

The Waters of the United States rule proposed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 2014 has been mired in fights in the House and Senate and now the courts. In fact, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued a slate of Clean Water Act permits at the beginning of 2017, any references to the controversial rule were not in evidence.

A new wrinkle for gas processors is a new EPA proposal in the first weeks of 2017 to include natural gas processing facilities in its Toxic Releases Inventory rules. This would mean processors could be added to operators having to meet reporting requirement under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act.

The EPA is giving affected parties a chance to file comments on the rule until March 7. The goal is to increase the amount of information available to public about any releases and waste management of chemicals used as part of the process.

The agency reports that about 265 gas processing plants would fall under reporting rules. They include plants that make, process or use 21 different chemicals covered under the rule including benzene, hydrogen sulfide, methanol, toluene and xylene.

The issue of reducing methane emissions also is a hot topic. Because the regulations regarding those emissions, like many EPA rulings, are being debated in Congressional committees, it has become difficult for some projects to move forward. Oil and gas experts counter EPA assessment of their industry’s contribution to methane emission and the buildup of greenhouse gases, saying the industry only accounts for about 3.4 percent of the total, which has been reduced 15 percent overall since 1990 even with a rising population.

Environmental concerns from the public have stalled some projects, including the Constitution and Atlantic Sunrise pipelines. Another standstill much in the news lately, is the Dakota Access Pipeline, which is passing through traditional tribal lands.

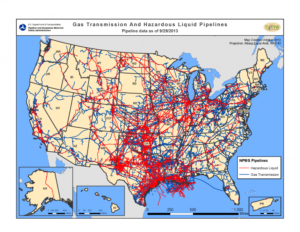

But new building of midstream infrastructure is moving forward, if somewhat hesitantly, because of the huge need for a way to move increased oil and gas production from U.S. shale plays.

About $640 billion in infrastructure is needed through 2035 to meet the needs of getting petroleum products to consumers in North America, according to a study by the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America. At least half of that would be for mainlines, laterals, processing, storage, compression and gathering lines. Another $59 million in investment is needed for natural gas liquids and the rest would come for the midstream operations associated with crude oil.